Rationing

Why didn’t Britain have enough food? (See also page 11 in the booklet)

Less than a third of the food available in Britain at the start of the war was produced at home. Enemy ships targeted incoming Allied merchant vessels, preventing vital supplies - including fruit, sugar, cereals and meat - from reaching the UK.

Because of this, and to ensure fair

distribution of supplies, the Ministry of Food

issued ration books to every person, and

families had to register at one shop.

Official rationing began on 8 January 1940 with bacon, butter and sugar. Rations were distributed by weight, monetary value or points. One person’s typical weekly allowance would be: one fresh egg; 4oz margarine and bacon (about four rashers); 2oz butter and tea; 1oz cheese; and 8oz sugar. Meat was allocated by price, so cheaper cuts became popular. Points could be pooled or saved to buy pulses, cereals, tinned goods, dried fruit, biscuits and jam.

Luxuries were in short supply too. Despite the stresses of wartime, the health of the poor improved.

People were encouraged to eat protein, carbohydrates, pulses and fruit and vegetables. Babies, pregnant women and the sick were allocated additional nutrients such as milk, orange juice and cod liver oil. Luxuries, including alcohol and cigarettes, weren’t officially rationed but were limited and expensive as factories focused on the war effort. From September 1939, petrol was only available for business or essential purposes. Furniture and clothing became utilitarian: pleats and turn-ups disappeared from trousers and garments were plain. Women painted gravy browning on bare legs as a replacement for silk stockings.

Restaurant food was curtailed by price (a maximum of five shillings per meal) and quantity, but eating out was popular with those who could afford it. Local authority-run ‘British Restaurants’ fed those bombed out of their homes and also provided cheap meals for workers. They were often set up in schools and church halls. By 1944 there were 2000 British Restaurants in London alone.

A healthier nation Digs For Victory

The pioneering Ministry of Food’s Dig For

Victory campaign encouraged self-sufficiency,

and allotment numbers rose from 815,000 to 1.4

million. Pigs, chickens and rabbits were reared

domestically for meat, whilst vegetables were

grown anywhere that could be cultivated. By 1940

wasting food was a criminal offence. As sugar

was in short supply, sweets were rationed from

July 1942 to February 1953. An attempt to

de-ration them in 1949 lasted just four months,

as demand far outstripped supply.

The resourceful use of rations

The Ministry of Food produced posters (above), leaflets and also Food Flashes, which were shown to 20 million cinema-goers from 1942 to 1946. Marguerite Patten’s cooking tips on the Home Service drew six million listeners daily. Homefront housewives had to be creative: ‘mock’ recipes included ‘cream’ (margarine, milk and cornflour) and ‘goose’ (lentils and breadcrumbs). Amongst other things, carrots replaced sugar in apricot tart and were also eaten on sticks as lollies. Powdered egg and Spam from the US were mainstays of the era. Despite the complexity, the queuing and the paperwork, many appreciated the fairness and equality of rationing.

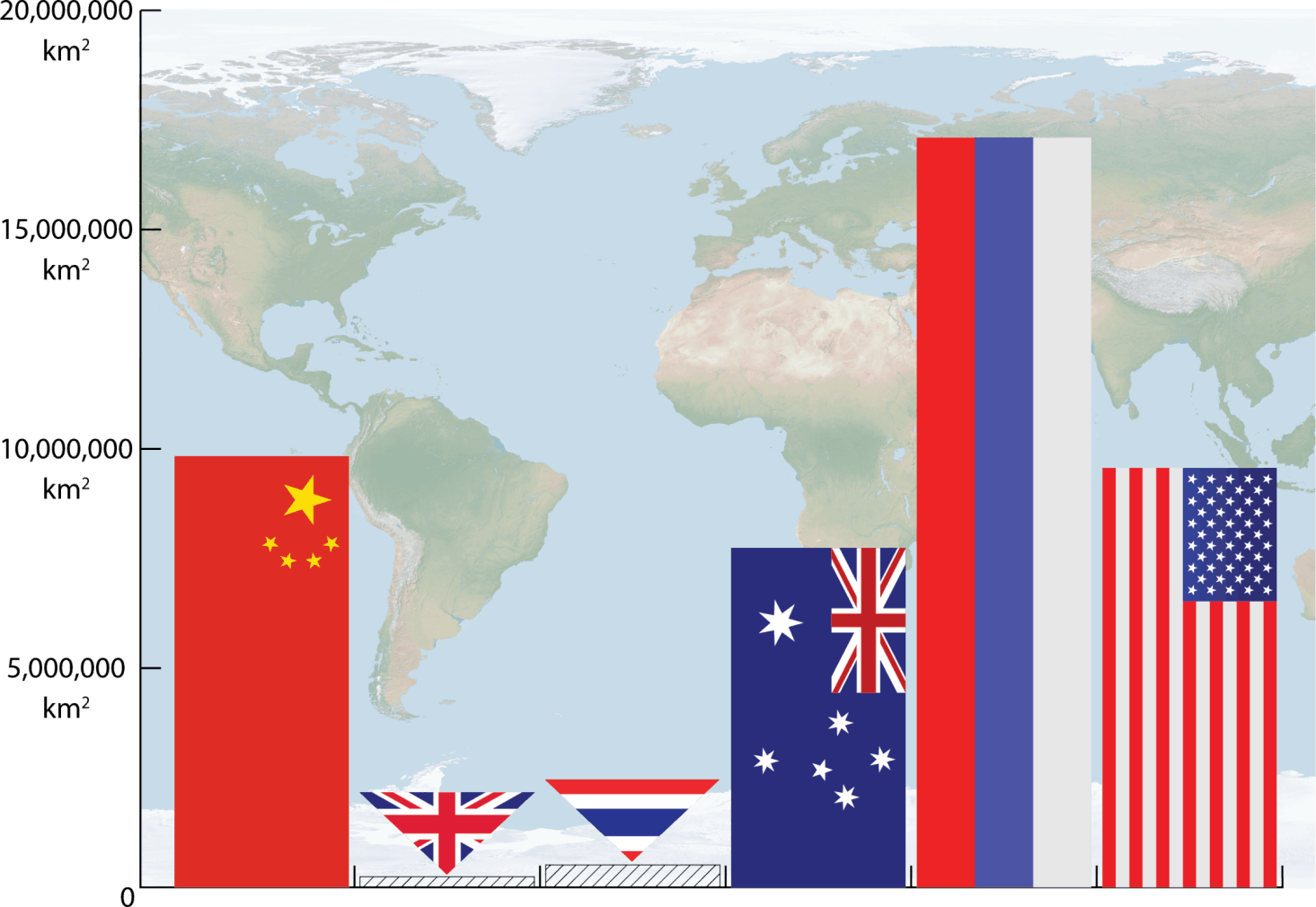

Why didn’t Britain have enough? Comparative

maps: