Evacuation 2

So, Operation Pied Piper meant that the children in areas designated 'danger areas' were to be sent to safe areas.

Who can tell me what 'designated'

means?

It means 'given a name'.

The country was divided into three main areas -

evacuation,

neutral and

reception.

An evacuation area was where

the government guessed the Germans would attack,

neutral areas were where the government thought

the Germans might attack and reception areas

were the areas thought to be safe from attack

and therefore areas where children could be

sent.

What sort of places would be ‘evacuation’

areas?

Large cities and industrial areas, but not only

London, but Birmingham (halfway up the country),

Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow. These were

areas from which people wold be removed.

What would a ‘neutral’ area be?

An area which had light industries or small

industries, not concentrated in a city or

certain area. These were areas from which people

would neither be sent, nor would these areas

receive evacuees.

Can you guess what a

‘reception’ area would be?

An area which would receive those people who

were evacuated from ‘evacuation’ (dangerous)

areas.

And what about a safe area?

A safe area was anywhere the Germans would have

no interest in attacking - countryside, areas

where there was no industry contributing to the

war effort or anywhere else where there was

nothing worth bombing.

Operation Pied Piper was designed to keep safe

the parts of the population who were

vulnerable.

The evacuees were divided into groups.

The first group was the school

children. In those days, you stayed at school

until just 14 - and then you could go to work or

for further study and then university. Most

people left at 14.

Here are two evacuee children - these are models but you can see the labels they had to wear.

The second group was ‘the infirm’. Someone who is ‘infirm’ is someone who is perhaps old, wobbly, disabled, or needs help getting around.

The third group was pregnant women. Obviously, as some men joined the forces, they had left behind their wives who had mysteriously become pregnant. Clearly they couldn’t move particularly quickly so they had to be evacuated.

The last group was mothers with babies or children under school-age (up to about 4 years old). This was the only group which were allowed to stay together when they were evacuated.

Every child - as you can see - had to have a label, Identity Card and a Ration book with them - often tied to them with string. WW2 was the only time in British history that Britons were required to have an identity card.

The problem was, sending children away without their parents - only with their teachers - that parents were reluctant to send their children away.

What does ‘to be reluctant’

mean?

It means not to be enthusiastic, not to want to

do something - unwilling.

What the government did was arrange their own

poster campaign to persuade parents that their

children would be safer away from danger areas.

It was also a propaganda campaign; if you

remember, that odd little man Dr Josef Goebbels

was in charge of propaganda against the Jews;

that was bad propaganda - but propaganda can

serve good purposes too.

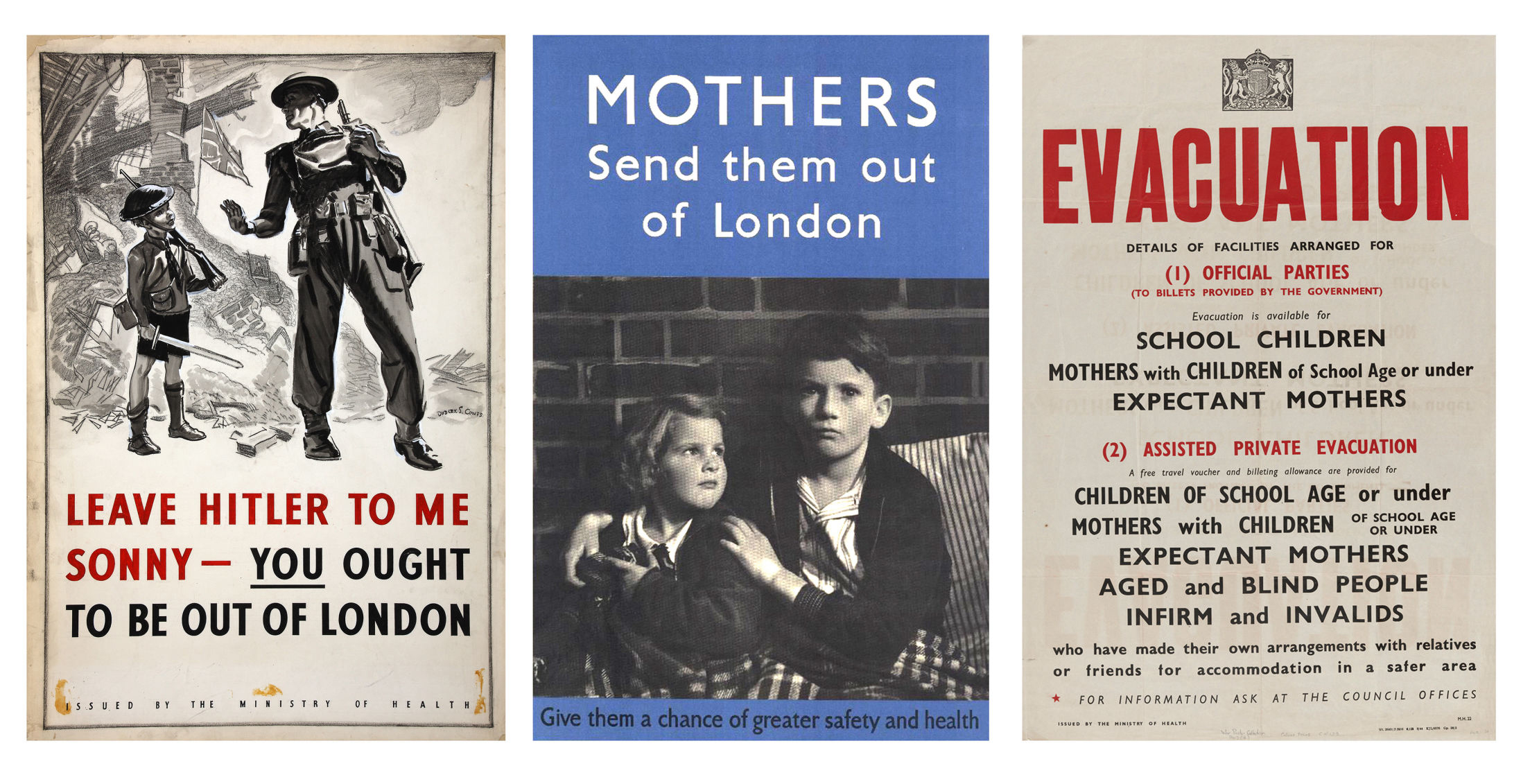

The posters were a bit ‘heavy-handed’.

What do you think

‘heavy-handed’ means’?

It means very obvious, almost too much, ‘over

the top’.

These three posters show government posters - they very much tell parents that they are being uncaring and putting their children in danger if they do not evacuate them.

The thing is, that it worked.

When war was declared in 1939, thousands of

children were evacuated within the first few

weeks. In fact, it started 2 days before war was

declared. Which was great!

However, there was a problem. The Germans

didn’t attack until 1940. We’ll deal with that

later.

The evacuation of children was actually really

well-organised, and the railways, buses and

other forms of transport all worked together to

get the children out of the danger areas.

However, as children, many people only

remembered chaos and disorder; but then, they

were children and didn’t have much idea what was

going on.

They were told to pack a suitcase, get their

ration books and ID cards, and go to their

schools early the next morning. There they were

given their labels and told absolutely not to

lose those labels.

Then they either walked to the local railway

station or buses arrived to take them to railway

stations and tearfully, mothers - and some

fathers - said good bye.

Evacuation was not for ever, and parents were

allowed to visit the children, but only once

they had arrived and sent their new addresses

home.

Most children seemed to think it was a great adventure, and some were devastated and upset. Teachers had to look after their class; even nuns and other women’s organisations helped out.